Three Reasons Why Knee Valgus Occurs During a Squat

Feb 11, 2022

Introduction:

Have you ever noticed how common knee valgus is around 90 degrees of hip flexion during a squat? If so, have you ever wondered why it occurs? We tend to be quick to blame weak muscles such as the glute max, glute med, and glute min as the main contributors to the observable compensation. However, to fully comprehend and beneficially educate your patient or client, blaming muscle weakness is only a small part of the much greater picture. In this article, you'll learn three reasons why knee valgus occurs during a squat.

Topics that will be discussed include:

- False Internal Rotation Strategies

- The influence of Knee Valgus from an Anterior Pelvic Tilt

- The influence of Knee Valgus from a Posterior Pelvic Tilt

If you're a visual learner, click the video below to watch these concepts:

Lower Extremity Arc of Motion:

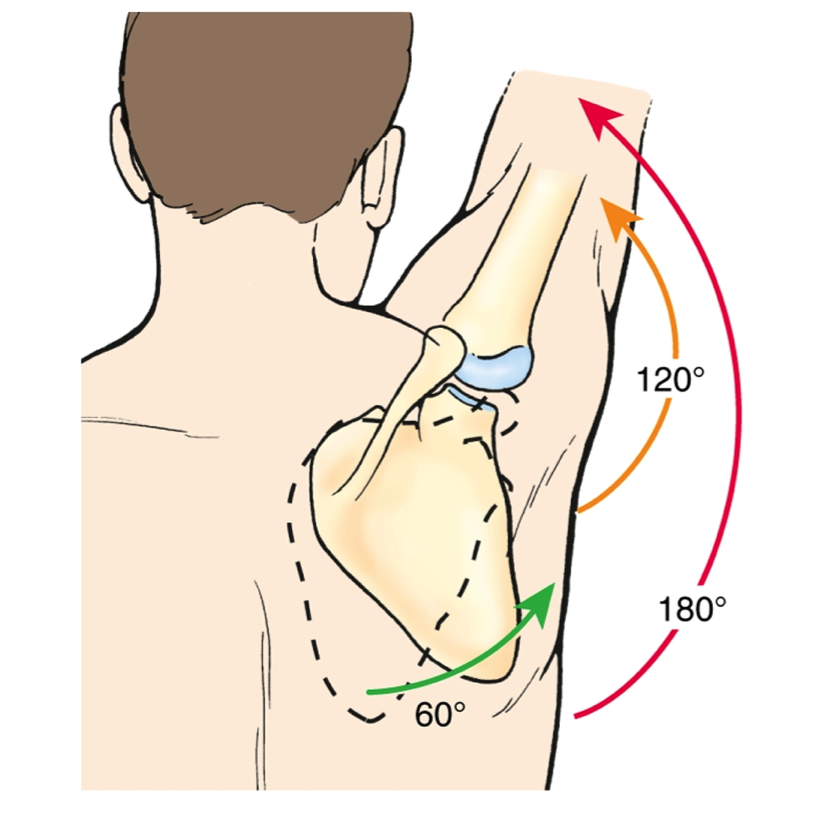

Before we can jump into the reasons of knee valgus, we first need to understand the lower extremity arc of motion. This concept that was popularized by Bill Hartman helps demonstrate normal vs abnormal biomechanical expectations throughout full hip flexion. It can be represented by the following:

- 0-60 Degrees of Hip Flexion: External Rotation Bias

- 60-90 Degrees of Hip Flexion: Internal Rotation Bias

- 90-120 Degrees of Hip Flexion: External Rotation Bias

In short, we see an internal rotation bias occur from 60-90 degrees because of the re-orientation of muscles. For example, the glute max, glute med, and piriformis re-orient from external rotators to internal rotators. More specifically, we can better understand this by looking at the piriformis. We can grossly call the anterior sacrum the origin and the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter as the insertion. As the piriformis approaches 90 degrees of hip flexion, the greater trochanter's line of pull changes towards a parallel direction with the entire muscle. The different angle creates the shift towards internal rotation when the piriformis contacts during this period of hip flexion (or of a squat).

The bottom line — to understand abnormal compensations (knee valgus during a squat), you must fully comprehend normal expectations (biomechanics).

False Internal Rotation Strategies:

The first reason why we see knee valgus occur is to deploy false internal rotation strategies. Remember, external rotation creates space while internal rotation produces power. So, when the body is in a compromised position whether it be from excessive weight, poor posture, or incorrect lifting technique — it will attempt to find strategies to develop power however it can.

At this point, you might be saying to yourself, "didn't he just say that at 90 degrees of hip flexion we bias IR, and knee valgus is an IR strategy?" Yes – you're right. The problem lies in the way that it's produced. In short, not all internal rotation is created equal – let me explain.

As the femur moves through 60-90 degrees of hip flexion, we should ideally see relative motions occur at the pelvis. These motions should include internal rotation, adduction, and extension. However, if the pelvis is unable to achieve these normal biomechanics then we'll see compensatory internal rotation — knee valgus. In other words, the femur internally rotates and produces "knee valgus" which moves the innominate bones in the same direction. However, in an ideal world the innominate bones should be in charge of the femur in a closed-chain exercise such as a squat.

Still, finding it difficult to visualize what "relative motion" at the pelvis means? Think of an example you're more familiar with — scapulohumeral rhythm. Most people have a better understanding of the relative motions that occur between the humerus and scapula. For example, as the humerus moves into flexion, we have biomechanical expectations of seeing upward rotation of the scapula. If the scapula is unable to move into full upward rotation then it makes sense that the humerus will compensate with internal rotation and demonstrate a decrease in the available range of motion. Well, this is the same problem that is occurring at the femur and pelvis!

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

In order to understand how an anterior pelvic tilt creates knee valgus, we need to first understand normal to explain abnormal:

1) What are the typical biomechanics associated with an anterior pelvic tilt?

When a patient or client has an anterior pelvic tilt posture, you will most likely see the following pelvis biomechanics:

- Sacral Nutation

- Innominate Internal Rotation

- Innominate Adduction

- Innominate Extension

Second, we expect to observe an overall internal rotation bias around 90 degrees of hip flexion during a squat.

You now know the normal findings and expectations to the above two questions. You also may be wondering why the internal rotation of the innominate bones is "bad" when it's expected at this point in the squat.

The answer: over-dominance

The posture of an anterior pelvic tilt becomes an over-dominant pattern — anything in excess creates problems.

Although internal rotation is desired at this point of the squat, the pattern creates a position of extreme posterior eccentric lengthening. The muscles on the posterior pelvis eccentrically bias as a result of their dominant sacral nutation. This puts the body in a position where it doesn't sense that it has adequate leverage to produce the power it needs. As a result, it will find leverage elsewhere – i.e internal rotation of the femur to create "knee valgus."

Posterior Pelvic Tilt

Just as we reviewed with the anterior pelvic tilt, let's begin with the same two questions to better understand normal to explain abnormal:

1) What are the typical biomechanics associated with a posterior pelvic tilt?

- Sacral Counternutation

- Innominate External Rotation

- Innominate Abduction

- Innominate Flexion

Conclusion

First, understand that knee valgus is the branch of the problem and the pelvis (axioskeleton) is the root. When we change our branch or "symptom" based perspective, we start thinking 3-dimensionally and addressing/understanding the true source.

From there, we can start respecting that the human body is simply trying to do what you are asking, but may not be starting in the optimal starting position or utilizing the right strategies.

So, the next time you see knee valgus during a squat, don't be so quick to simply throw a band around your patient or client's knees — seek to understand what they truly need in order to fix the problem.

Interested in concepts like this one? I discuss this in much more detail in The Performance Redefined Online Course and provide specific exercises to help you increase your coaching confidence to build movement mastery!

Enjoy learning practical topics like this one? Join The PR Club for Free to gain instant access to 100+ educational movement videos just like this!